Today, nearly 50 million annual trips occur between Los Angeles and Las Vegas – over 85% of them by automobile – a trip which is unpredictable, unreliable and challenged by congestion. Brightline West expects to serve 9 million one-way passengers annually.

The idea of a fast, reliable rail link between Southern California and Las Vegas has been kicking around for decades, resurfacing every time I-15 turns into a weekend parking lot. What’s different now is that the project is no longer a speculative concept or a string of glossy renderings. The line now has a defined route, named stations, major funding commitments in place, and years of field work already underway along the corridor.

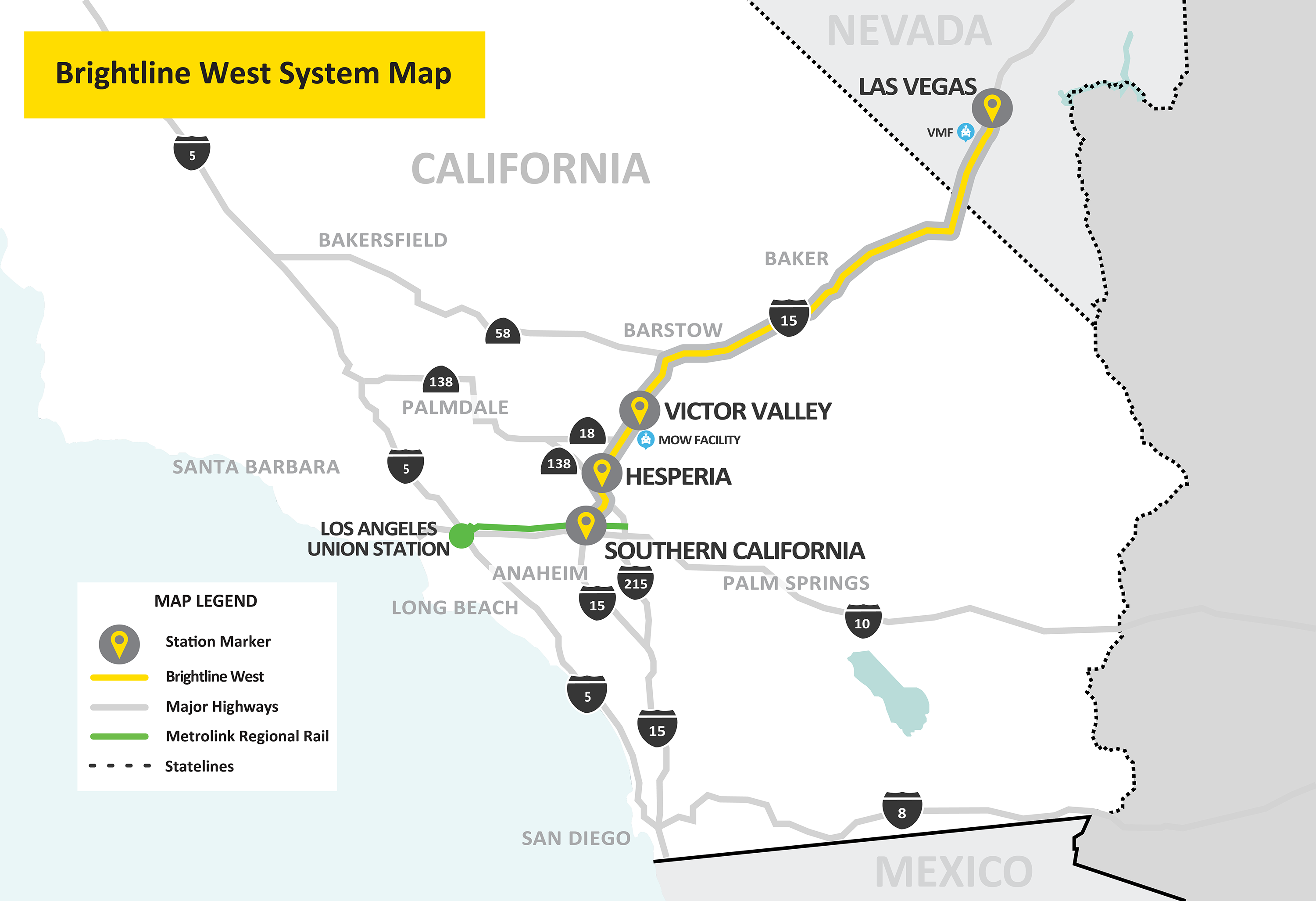

The project most people mean when they say “the train to Vegas” is Brightline West, a privately led high-speed rail line planned to connect Las Vegas with the Los Angeles region by running largely in the median of Interstate 15. The route is designed to be about 218 miles long, built for all-electric trains capable of speeds above 200 miles per hour. The headline promise has always been simple: turn a drive that can swing from four hours to “who knows” into a trip measured in roughly two hours, with a schedule that doesn’t depend on traffic, holiday gridlock, or the weather.

One of the biggest points of confusion is the “Los Angeles” part of the route. The southern terminus is planned for Rancho Cucamonga, not downtown Los Angeles. That choice is strategic: building straight into the most complex parts of the LA Basin would add time, cost, land constraints, and political headaches. Instead, the plan is to plug into an existing regional rail hub so travelers can reach the station via Metrolink and other local connections, then board the high-speed service for the desert run. For Angelenos, that means the trip becomes two steps: getting to Rancho Cucamonga, then taking the high-speed train to Las Vegas. The total door-to-door time will depend heavily on how seamless the local connection is and how frequently trains run.

Las Vegas, meanwhile, is positioned to be a more straightforward arrival experience. The planned station site is south of the Strip on Las Vegas Boulevard, intended to function as a purpose-built gateway for visitors, with space designed for the kind of passenger flow Vegas is used to handling. In between, the line is expected to include stations in the High Desert, with Apple Valley and Hesperia commonly cited as key stops. The point isn’t just to serve Vegas tourists; it’s also to build a spine of mobility through a corridor where growth has been strong and where I-15 is often the only practical option.

A major milestone arrived when the project secured a multibillion-dollar federal grant agreement through a partnership with the Nevada Department of Transportation. That grant is aimed at final design and construction and has helped shift the project from aspiration to execution. The financing plan also leans on private capital, including federal private-activity bond capacity, a structure often used to fund large infrastructure that has a defined revenue model. The mix matters because it affects how quickly the project can move and how insulated it is from the start-stop cycles that have defined many American megaprojects.

Groundbreaking ceremonies in 2024 marked the public start of construction, but the more telling signs of progress have been the less glamorous ones: surveys, geotechnical work, utility investigations, and on-the-ground field activity in both Nevada and California. This kind of work is where a project either proves it can navigate reality or gets swallowed by it. The corridor may look simple on a map—follow I-15, keep it straight—but the details are complicated: bridges, interchanges, drainage, utilities, soil conditions, maintenance facility needs, construction staging, safety requirements, and the constant challenge of doing heavy work adjacent to one of the busiest travel highways in the West.

“The schedule has also become clearer—and less dreamy. For years, the unofficial hype line was “in time for the Olympics,” with the 2028 Summer Games in Los Angeles serving as a symbolic deadline. The more recent planning has shifted expectations toward the end of the decade, with late 2029 now widely associated with the projected start of service.”

The schedule has also become clearer—and less dreamy. For years, the unofficial hype line was “in time for the Olympics,” with the 2028 Summer Games in Los Angeles serving as a symbolic deadline. The more recent planning has shifted expectations toward the end of the decade, with late 2029 now widely associated with the projected start of service. That change doesn’t necessarily signal trouble; it reflects the reality of building a high-speed rail system from scratch in the U.S., with new stations, new track, new signaling, new power systems, extensive testing, and the necessary approvals layered on top. The closer a project gets to real construction, the more honest the timeline tends to become.

There’s also an environmental story running underneath the transportation story. A line cutting across the Mojave Desert raises unavoidable questions about habitat, wildlife movement, and long-term impacts. Plans for wildlife overcrossings and other mitigation measures have been part of the project’s development, aimed at reducing the barrier effect that rail infrastructure can create for species that already navigate a fragmented landscape. This is not just an add-on; it’s the kind of requirement that can shape design, budget, and construction sequencing.

So what is the “update” right now? The most meaningful update is that the project appears to be in the grinding middle stage between announcement and arrival—the stage where timelines get revised, financing gets finalized, construction plans get tested in the field, and the public begins to see more than press conferences. The late-2029 target is a practical marker to watch, but the more immediate tells will be visible construction milestones in 2026 and 2027: sustained heavy work along the corridor, station progress that’s impossible to miss, and major procurement and testing steps for the trains themselves.

For Southern California travelers, the eventual success of the service will be judged on a few simple questions. How easy is it to get to Rancho Cucamonga without a car? How frequent are departures on peak weekends? What does the pricing look like compared to driving, flying, or taking a bus? How smooth is the last mile in Las Vegas? If those pieces land, the train becomes more than a novelty—it becomes a new default for one of the most traveled leisure corridors in the region.

For now, the clearest takeaway is that the Vegas train is no longer a “maybe someday” concept. It’s a real infrastructure project with real constraints, real funding, and a real timeline that has settled into the end-of-decade range. The next year or two will determine whether it keeps momentum through the hardest part: turning plans into track, stations, systems, and a service that can run safely at true high-speed—day after day, weekend after weekend—on the one route where demand has never been the problem.